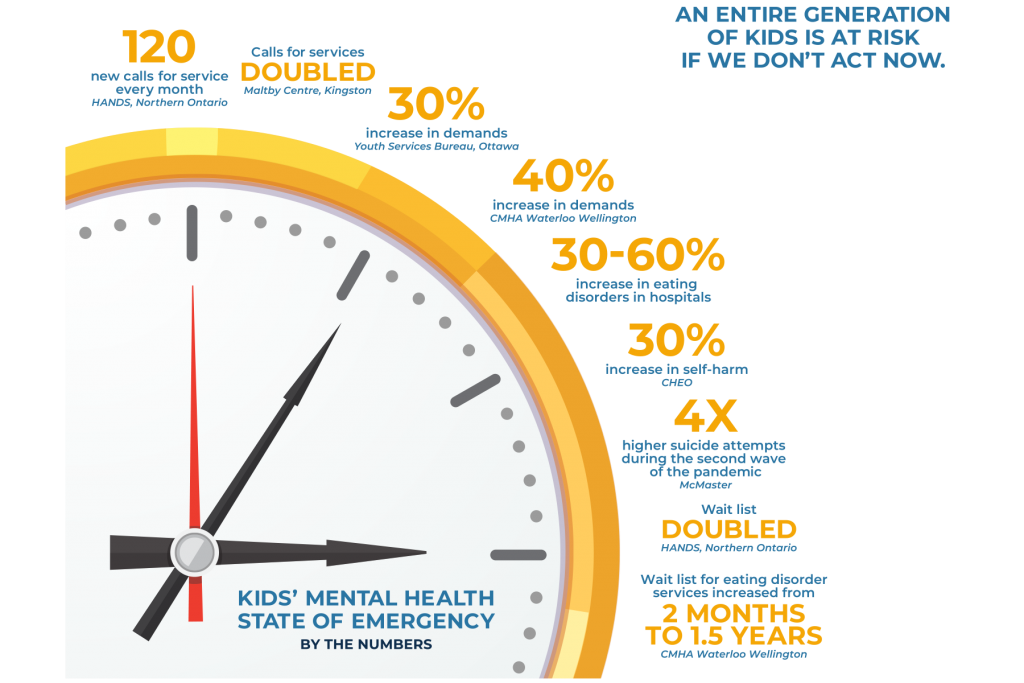

The pandemic has pushed demand for children and youth mental health services through the roof in Ontario.

Even before COVID-19, kids struggled to get access to timely care for mental health issues. Today, child and youth mental health centres are overwhelmed by the sheer number of young people needing help for serious and complex problems like eating disorders, self-harm and suicide attempts.

As just one example of what child and youth mental health centres across Ontario are experiencing, HANDS, The Family Help Network, in Northern Ontario is seeing 40 new clients a week – that’s four times the number at the start of the pandemic. The organization’s waitlist for intensive services has soared from an average of 3-6 months to as long as a year.

An entire generation of kids is at risk

An entire generation of kids is at risk

Trish Benoit, director of children and youth mental health at HANDS Family Health Network, says the organization has seen a surge in demand for its counselling clinics that offer short-term interventions limited to three sessions. But it is also seeing a greater need for longer-term counselling. “The actual need for this service far exceeds our capacity to deliver it,” she says.

4X as many kids receiving mental health support than before in Northern Ontario

Kathy Hewitt, a child and family therapist with HANDS Family Health Network, works primarily with children aged five and under. Since the pandemic began, she has noticed fewer programs and services available to parents, such as daycares or places for children to socialize.

Instead, as children have had their routines disrupted, parents are increasingly turning to mental health workers for support. The field is under strain and struggling to keep up staffing to match the increased demand. “We are short-staffed, unable to recruit people,” she says. “Our jobs tend to be lower paid compared to mental health jobs in education and other health sectors.”

Third-party referrals — those from family doctors and school officials — often have waitlists of a month. But those referrals have increased wait times for parents seeking help for their children without a third-party referral. “It’s very discouraging to tell a family that unless you’re suicidal, you have to wait a year for treatment,” Kathy says.

Families are having trouble accessing mental health supports across Ontario.

Vicki is one of the parents who has struggled to access care for her child. Her 16-year-old son has faced challenges as both schools and mental health treatment have gone virtual. “His suicidal ideation increased and his sense of loneliness and isolation has increased,” she said. Vicki shared her experiences with the Brampton Guardian.

The pandemic reduced the number of individual counselling sessions, shifting treatment more toward group sessions, which doesn’t work for every child. But when a young person appears to be disengaging from group therapy, mental health workers sometimes decide they aren’t benefiting from treatment and give their spot to another child, Vicki says.

Meanwhile, after-hours mental health services have refused to help Vicki’s son if he is threatening to harm himself or others, leaving her to contact police as her only option.

More kids experiencing eating disorders

When stress from the loss of social connections caused emotional dysregulation to surface that included, depression, anxiety and self-harm, one 15-year-old also developed an eating disorder last year. Her mother Lianne Phillipson sought help for her daughter from George Hull Centre. Lianne also participated in the Sashbear program learning the same DBT skills that her daughter was learning from George Hull.

While mother and daughter both found the services helpful and supportive, the fact that her daughter’s sessions were virtual created extra challenges.

“The group sessions, being online, didn’t foster the connection that we both believe could have helped more,” Lianne says. “It was an advantage for her to go through the program, but she says herself that she’s not sure what impact it had.”

Lianne says it would have been easier to get treatment for her daughter if a mental health worker had been assigned to help them navigate the available services

Also important, she says, is education for parents in how to recognize that their child is having a mental health crisis – such as how to identify a panic attack – along with information about alternatives to therapy, such as changes to diet and exercise routines.

“The more parents know, the more they can help their kids, or find the right help,” Lianne says.

Read more: More severe mental health issues reported in kids.

Find Help

If you or your child are in need of mental health supports, reach out to a child and youth mental health centre in your community. Find help. Also, read more about how to recognize that your child needs help.

Take the Pledge

Ontario is facing a kids’ mental health crisis. To raise awareness, we are sharing stories from families who are a part of our Parents for Children’s Mental Health peer support chapters. These are real parents, real children – and real issues. Our kids can’t wait anymore for mental health care. Families should be able to access kids’ mental health treatments wherever they are, when they need it.

We are calling on Ontario’s political parties to Take the Pledge for kids’ mental health. You can help. Ask your MPP candidates to Take the Pledge.

0 Comments